Freedom and equal rights are societal norms most of us don’t think twice about.

But we should.

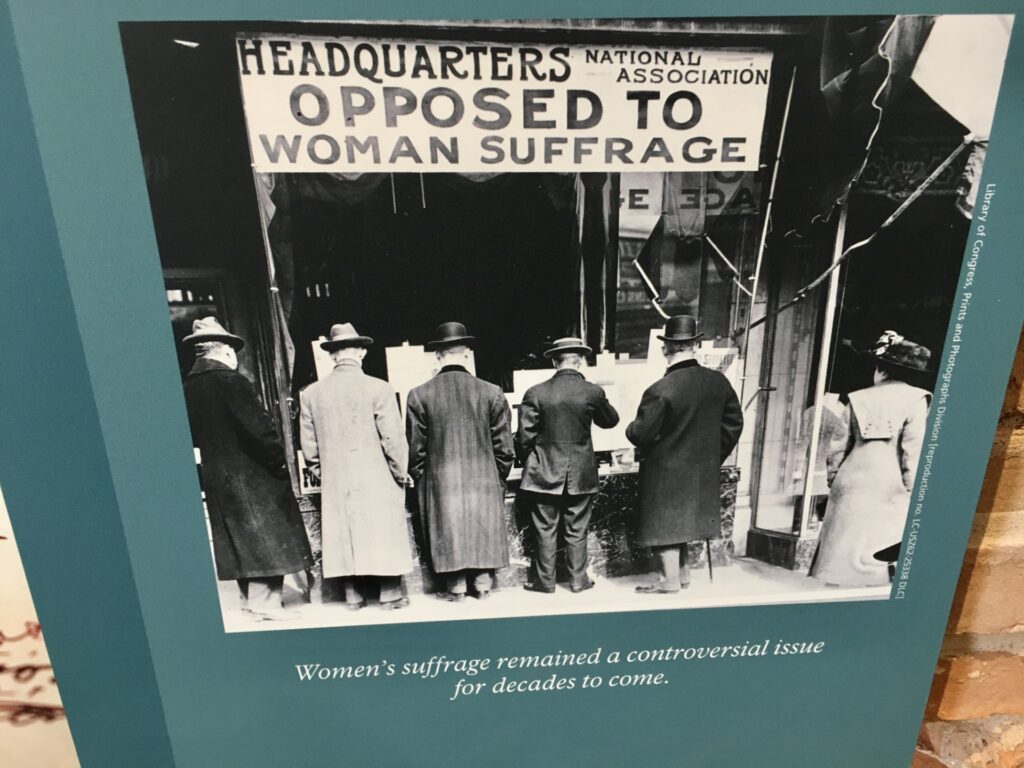

It was only around 160 years ago that slavery was abolished in the United States. And women did not get the vote until 1920.

In the 1800s abolitionists and suffragettes fought to change the course of history in the United States. The fiery orators and passionate believers who brought these movements to life lived in cities in New York’s Finger Lakes region. These included Rochester, Elmira, Fayetteville, Seneca Falls, and Auburn.

To learn more about their struggles, my husband and I took a road trip from Toronto to explore these incubators of agitation. Starting in Rochester, an easy three-hour drive, we wanted to learn how the bedrock of North American social justice came about.

It was a refresher that I think many people would benefit from today.

Why the Finger Lakes and Rochester?

The city of Rochester was America’s first boom town due to the Erie Canal. Shovels hit the earth in 1817 and it was completed in 1825. All done by hand.

The canal acted as the super hi-way of the 19th century, transporting goods between New York City, through Upper New York State, and on to the Great Lakes. It was a mover of goods, services, entrepreneurs, ideas, and idealists.

The Birth of Women’s Rights and A Bond with Abolition

Susan B. Anthony, the voice of the women’s rights movement, had a home base in Rochester. So did abolitionist and author Fredrick Douglass, who had escaped slavery in Maryland. Sympathizer and author Mark Twain lived with his wife in Elmira for a time and wrote many of his beloved novels there. Harriet Tubman, a fearless Underground Railroad conductor, lived out her later years in Auburn.

Susan B. Anthony’s Legacy

Brought up to believe women and men of all backgrounds deserved equal rights. She started as an abolitionist, became involved in the Temperance movement, and then began to agitate for women’s rights and suffrage.

Docent Beryl Brock led us through the house and pointed out Anthony’s alligator bag that never left her side on her many speaking tours across the country.

Her colleague Elizabeth Cady Stanton started the suffragette movement and convinced Anthony to come on board. Stanton was married with seven children so Anthony, who was single, was given the role of traveling spokesperson. She endured many challenges but kept on fighting until she died in 1906.

Anthony’s friend, Frederick Douglass, often visited her in this home.

Douglass is buried in the city’s Mount Hope Cemetery, as is Anthony.

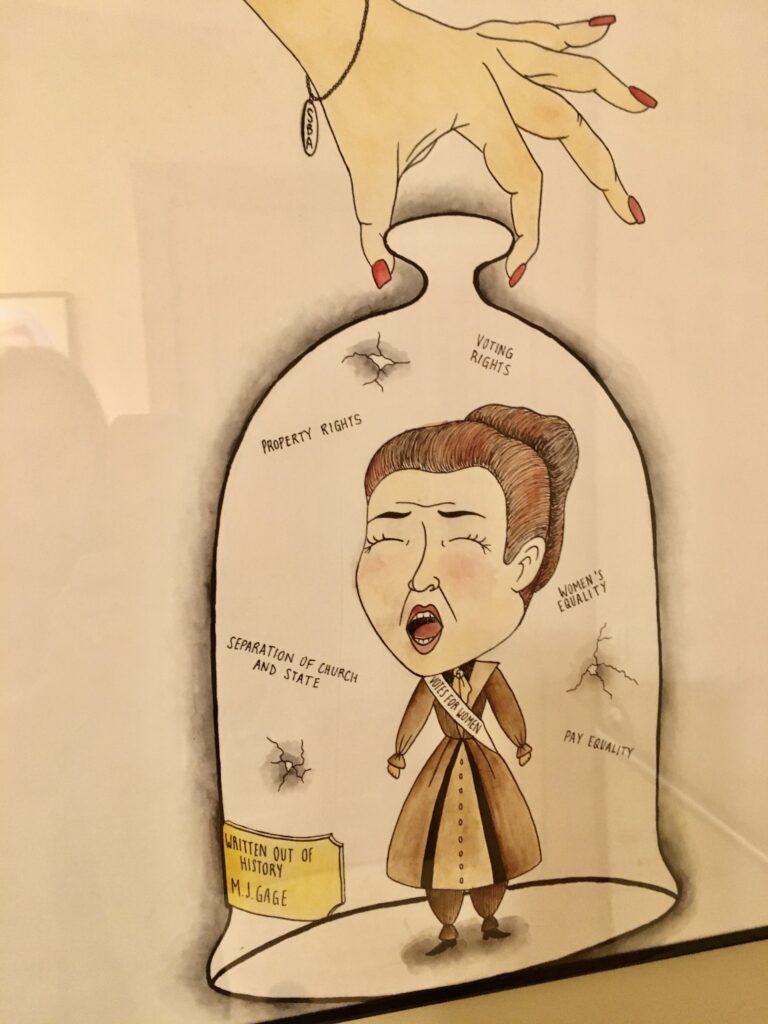

Susan B. Anthony’s Antithesis

Matilda Joslyn Gage was a suffragette and abolitionist who was thwarted by Anthony. Exhibits in Gage’s home, now a museum in Fayetteville, showed her to be integral to the women’s rights movement at the beginning. But she did not lean into the religious groups that Anthony had corralled from her Temperance connections. Anthony was determined to bring them on board to bring more pressure to the government and force them to give women the vote.

Gage believed church and state should be separate and eventually, she was pushed out from Anthony’s inner circle.

First Convention for Women’s Rights

In Seneca Falls, we saw where the first Women’s Rights convention was held in 1848 at the Wesleyan Chapel. Unfortunately, the chapel was not original, but there were plenty of key landmarks to see within the city’s Women’s Rights National Historical Park including the Visitor Center, Elizabeth Cady Stanton House, and Declaration Park.

Across the river, we also peeked into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

Native American Heritage and Women’s Rights

Traveling 45 minutes west to Ganondagan, we came to the Seneca Art & Culture Center which opened in 2015.

Exhibits honored the region’s Seneca Nation, the largest group in the Iroquois Confederacy or Six Nations. Iroquois is a word of French origin. A more correct term would be Houdenashonée, meaning “people of the longhouse.”

The property featured a long house that would have housed around 40 people.

Kristen Asche, a park and recreation aide at the center, told us that the Houdenashonée were way ahead of the suffragettes.

“The women owned their homes and had full rights to their bodies. This longhouse would have belonged to a grandmother and her daughters. All the men who lived there would be husbands from other clans,” she explained.

Asche also noted that the Houdenashonée government structure is one of democracy and was the model for the U.S. Constitution.

John W. Jones Freedom Seeker

I had never heard of African-American John W. Jones before, but stopping at his former home in Elmira, I learned much about the outspoken abolitionist.

“He was born a slave in Virginia to a kindly old spinster who taught him to read and write,” said Tamila Aaron, president of the Board of Trustees, John W. Jones Museum.

Plaques explained how, after escaping from Virginia, Jones arrived in Elmira in 1844 at age 27. He became sexton of the First Baptist Church and was responsible for the graveyard. At night he was a conductor on the Underground Railroad and aided in the flight of hundreds of freedom seekers.

Eventually, he became a sexton of Woodlawn Cemetery, where almost 3,000 Confederate troops were buried during the Civil War. Most died after being held in the notorious Elmira Civil War Prison Camp. Jones buried every man with dignity. Due to his precise records, the burial site became a federally recognized cemetery.

Mark Twain’s Creative Refuge

Mark Twain was also an area mover and shaker.

At Elmira College Dr. Matt Seybold, associate professor of American Literature and Mark Twain Studies, explained Twain’s connection to the area.

“His wife Olivia was from here. Her father Jervis Langdon was a rich coal baron and abolitionist. They lived on the family farm with Olivia’s sister Susan and her husband Theodore for a time,” noted Seybold.

Twain, whose real name was Samuel Clemons, wrote in a structure resembling a paddle wheeler’s pilot house outside the farmhouse. Some of his most beloved works, including Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn were penned here.

Known as the Mark Twain Study, it now sits on the Elmira College campus.

Harriet Tubman’s Final Resting Place

One of the most famous conductors on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman escaped slavery in Maryland and eventually ended up in Auburn.

Justin Harris, with Conductor Tours, took us on a walking tour of key Harriet Tubman locations. We started at the New York State Equal Rights Heritage Center and admired the Harriet Tubman statue outside.

“This is the street she was known for riding her pig on the way to the market,” Harris noted.

Passing the William H. Seward House Museum and Gardens, Harris explained that the former Secretary of State to Abraham Lincoln and his wife were friends of Tubman’s. Staunch abolitionists, they harbored many freedom seekers.

We also saw the Presbyterian Church where Tubman married Nelson Davis and AME Zion Church where she worshipped. The house where she lived was being restored, but we were able to take a peek around the home for the elderly she had built on her property.

Our final stop was Fort Hill Cemetery where she and some of her family are buried.

Fighting the Fugitive Slave Act in Syracuse

Our final stop was Syracuse. A highlight was the Jerry Rescue Monument in Clinton Square. It was created in honor of William Henry from Missouri. Henry’s mother was a slave owned by his father in Missouri. After his father died he was inherited by his father’s white step-son. Henry escaped to Syracuse where he worked at a cooperage.

New York was a free state then, but the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed slave hunters to capture escapees and return them to owners in the South. Henry was recognized and his owner demanded him back. Brought before a judge, Henry was incarcerated. But, in defiance of the act, the citizens of Syracuse stormed his jail cell and helped him escape to Canada.

Bravery and determination helped shape the United States as a country that valued treating others with respect and dignity.

Fighting for fairness was not easy then. And it’s not easy now.

The Finger Lakes legacy reminds us why we can’t take the freedoms and rights we have now for granted.